How Boxing Weight Classes Work

A weight class is a defined upper limit. If a division tops out at 147 pounds, a fighter must weigh 147 or less at the official weigh-in, typically held the day before the fight. Miss weight, and the consequences range from financial penalties to losing eligibility for a title.

The system exists for one fundamental reason: safety. A 130-pound fighter absorbing punches from a natural 160-pounder faces exponentially greater risk of serious injury. Weight classes create competitive balance by ensuring fighters face opponents of roughly similar size and power.

That said, boxing’s weight class structure has never been static. Divisions have been added, renamed, and reshuffled for over a century. What started as a straightforward system has become one of the most layered organizational frameworks in all of sports.

A Brief History of Boxing’s Weight Divisions

For most of boxing’s bare-knuckle era, there were no formal weight classes at all. Fighters simply fought whoever was available. The concept of organized divisions began taking shape in the late 1800s, when the sport started codifying rules under the Marquess of Queensberry framework.

By the early 20th century, boxing had settled into eight recognized divisions: flyweight, bantamweight, featherweight, lightweight, welterweight, middleweight, light heavyweight, and heavyweight. These divisions served the sport well for decades.

The expansion started in the mid-20th century. The WBC introduced the super bantamweight and super featherweight classes in 1976. The cruiserweight division was established in 1979 to bridge the enormous gap between light heavyweight (175 lbs) and heavyweight (then unlimited from 175+). Super flyweight, super lightweight, super welterweight, and super middleweight followed over the next two decades.

The lower-weight divisions — minimumweight, light flyweight — were added largely to serve the thriving boxing scenes in Asia and Latin America, where elite fighters frequently competed at weights well below the traditional flyweight limit.

Critics have long argued that 17 divisions are too many. With four major sanctioning bodies (WBC, WBA, IBF, WBO) each crowning a champion in every weight class, the sport can have 68 or more “world champions” at any given time. That dilution is one of the things Zuffa Boxing is now directly targeting.

All 17 Boxing Weight Classes

The following table lists every recognized weight class in professional boxing, from the lightest to the heaviest, along with the weight limit and notable champions who have defined each division.

| Division | Weight Limit | Notable Champions |

|---|---|---|

| Minimumweight (Strawweight) | 105 lbs / 47.6 kg | Wanheng Menayothin, Knockout CP Freshmart |

| Light Flyweight | 108 lbs / 49 kg | Michael Carbajal, Ricardo Lopez |

| Flyweight | 112 lbs / 50.8 kg | Jimmy Wilde, Pancho Villa, Roman Gonzalez |

| Super Flyweight | 115 lbs / 52.2 kg | Srisaket Sor Rungvisai, Juan Francisco Estrada |

| Bantamweight | 118 lbs / 53.5 kg | Naoya Inoue, Eder Jofre, Carlos Zarate |

| Super Bantamweight | 122 lbs / 55.3 kg | Wilfredo Gomez, Marco Antonio Barrera, Guillermo Rigondeaux |

| Featherweight | 126 lbs / 57.2 kg | Willie Pep, Salvador Sanchez, Prince Naseem Hamed |

| Super Featherweight | 130 lbs / 59 kg | Floyd Mayweather Jr. (early career), Manny Pacquiao, Acelino Freitas |

| Lightweight | 135 lbs / 61.2 kg | Roberto Duran, Benny Leonard, Pernell Whitaker |

| Super Lightweight (Jr. Welterweight) | 140 lbs / 63.5 kg | Aaron Pryor, Kostya Tszyu, Josh Taylor |

| Welterweight | 147 lbs / 66.7 kg | Sugar Ray Robinson, Sugar Ray Leonard, Floyd Mayweather Jr. |

| Super Welterweight (Jr. Middleweight) | 154 lbs / 69.9 kg | Thomas Hearns, Oscar De La Hoya, Jermell Charlo |

| Middleweight | 160 lbs / 72.6 kg | Marvelous Marvin Hagler, Carlos Monzon, Bernard Hopkins |

| Super Middleweight | 168 lbs / 76.2 kg | Joe Calzaghe, Andre Ward, Canelo Alvarez |

| Light Heavyweight | 175 lbs / 79.4 kg | Archie Moore, Roy Jones Jr., Dmitry Bivol |

| Cruiserweight | 200 lbs / 90.7 kg | Evander Holyfield, Oleksandr Usyk, Jai Opetaia |

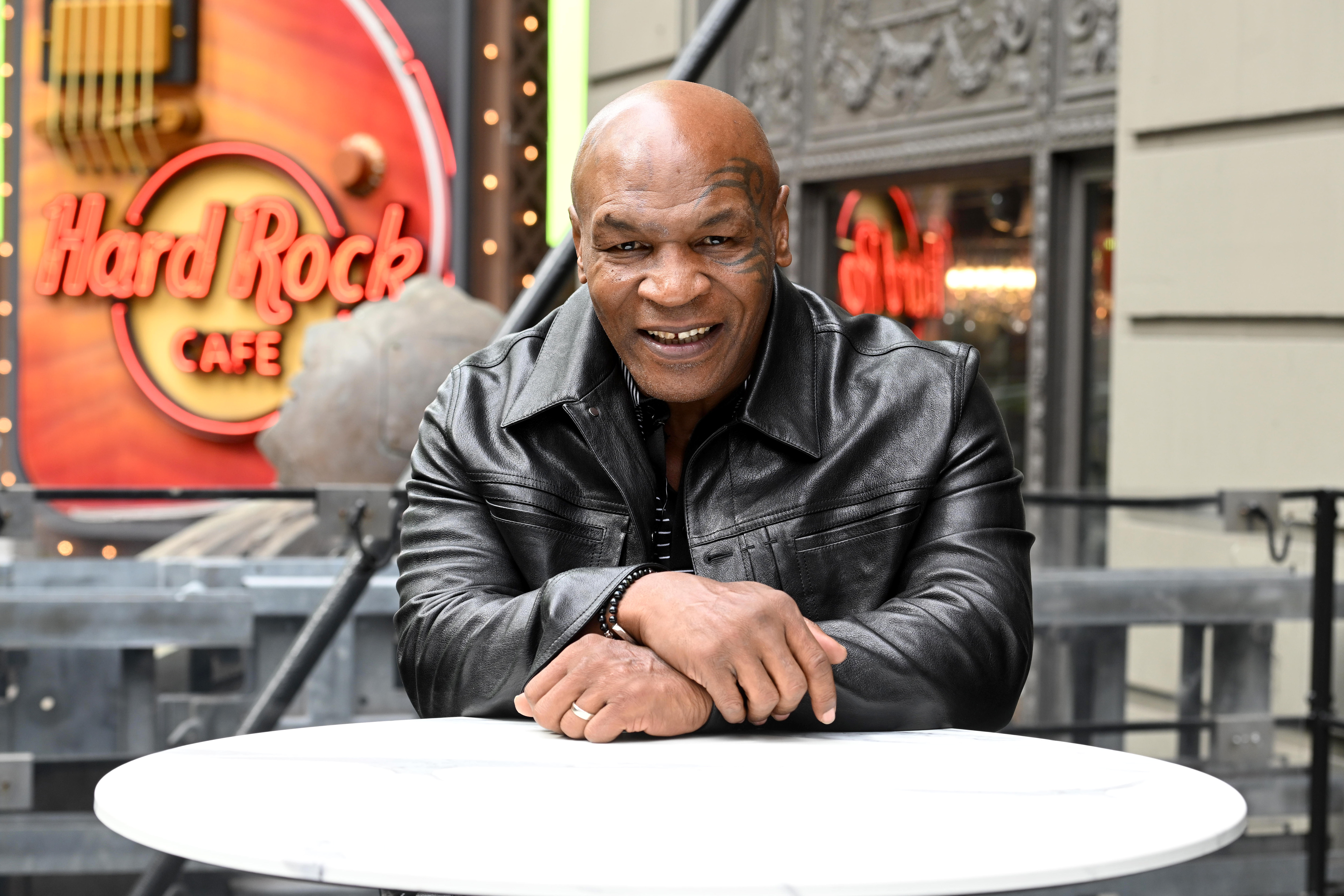

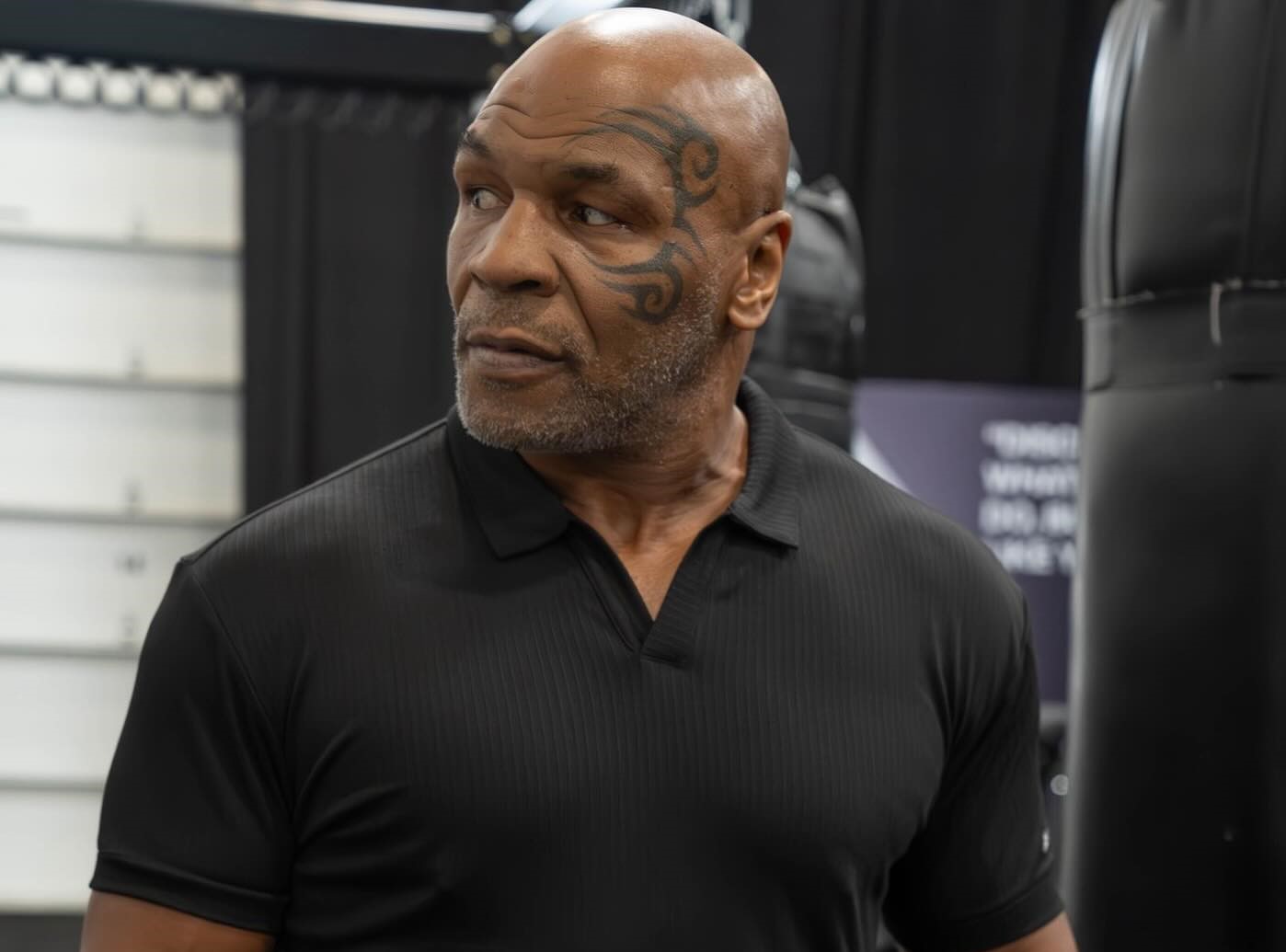

| Heavyweight | 200+ lbs / 90.7+ kg | Muhammad Ali, Mike Tyson, Lennox Lewis |

Division Breakdowns: The Full Picture

Heavyweight (200+ lbs / Unlimited)

The glamour division. Heavyweight has always been boxing’s most visible weight class, home to the sport’s biggest cultural figures — Muhammad Ali, Joe Louis, Mike Tyson, Lennox Lewis. There is no upper weight limit, which means heavyweights can range from a lean 200 pounds to well over 270. The division was historically defined as anything above 175 pounds until the creation of the cruiserweight class in 1979, which established the current 200-pound floor.

Cruiserweight (200 lbs / 90.7 kg)

Created to solve a real problem: 190-pound fighters were getting destroyed by 240-pound heavyweights. The WBC established the cruiserweight division in 1979, and it quickly produced stars like Evander Holyfield, who used the division as a launching pad to heavyweight glory. More recently, Oleksandr Usyk followed the same path, dominating at cruiserweight before moving up to become undisputed heavyweight champion. Jai Opetaia currently holds the IBF title and is set to fight for Zuffa Boxing’s inaugural cruiserweight belt on March 8, 2026.

Light Heavyweight (175 lbs / 79.4 kg)

One of boxing’s original eight divisions and consistently one of its most competitive. Light heavyweight has produced legends across every era — from Archie Moore’s record 141 knockouts to Roy Jones Jr.’s athletic dominance in the 1990s. The current landscape is shaped by Dmitry Bivol and Artur Beterbiev, whose styles and skills make 175 one of the deepest divisions in the sport right now.

Super Middleweight (168 lbs / 76.2 kg)

Added in 1984, super middleweight has become one of boxing’s most high-profile divisions thanks largely to Canelo Alvarez, who unified all four belts at 168. Joe Calzaghe retired undefeated as a super middleweight, and Andre Ward dominated the division before moving to light heavyweight. Notably, Zuffa Boxing does not recognize 168. Fighters who have built careers at super middleweight will need to move down to 160 or up to 175 under the Zuffa system.

Middleweight (160 lbs / 72.6 kg)

Middleweight is where boxing’s pound-for-pound debates often live. Sugar Ray Robinson, widely regarded as the greatest fighter ever, made his legend largely at 160. Marvelous Marvin Hagler, Carlos Monzon, and Bernard Hopkins all defined eras at middleweight. The division carries enormous historical weight and remains a marquee class. Callum Walsh, who was fighting at 154, moved up to 160 specifically to compete under Zuffa Boxing’s structure.

Super Welterweight / Junior Middleweight (154 lbs / 69.9 kg)

The 154-pound class has produced spectacular action fighters and is one of boxing’s most active divisions. Thomas Hearns, Oscar De La Hoya, and Jermell Charlo all held titles here. But under Zuffa’s eight-division model, 154 does not exist. Fighters at this weight face a choice: cut to 147 and compete against natural welterweights, or move up to 160 and fight bigger middleweights.

Welterweight (147 lbs / 66.7 kg)

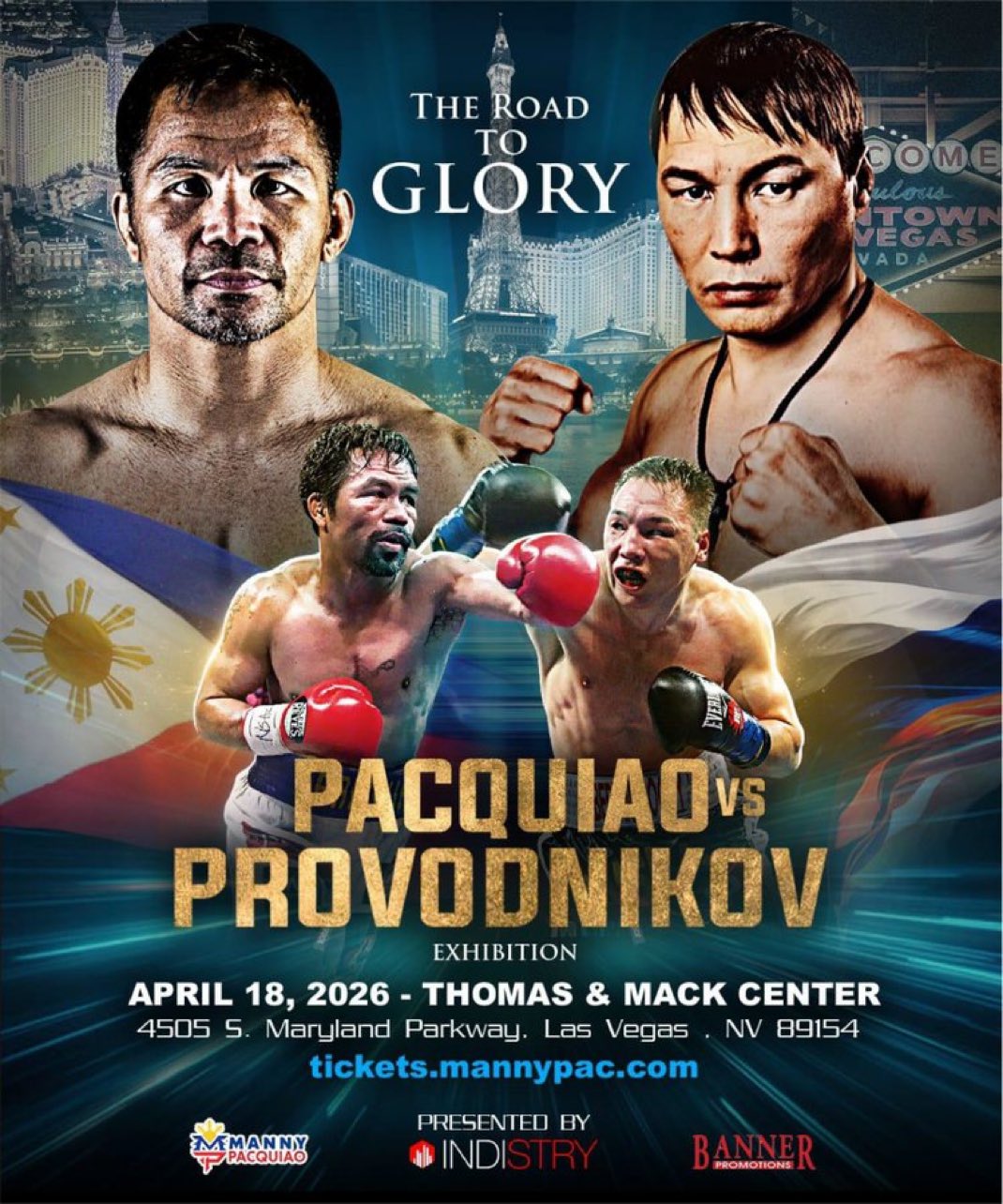

Arguably the most talent-rich division in boxing history. Sugar Ray Robinson, Sugar Ray Leonard, Thomas Hearns, Floyd Mayweather Jr., Manny Pacquiao — the list of all-time greats at 147 is staggering. Welterweight consistently produces the sport’s biggest pay-per-view draws and most competitive matchups. It is one of the eight divisions Zuffa retained.

Super Lightweight / Junior Welterweight (140 lbs / 63.5 kg)

The 140-pound division has been home to some of the sport’s most exciting fighters: Aaron Pryor, Kostya Tszyu, and more recently Josh Taylor, who became undisputed champion at 140 in 2021. Zuffa does not recognize this weight class. Fighters at 140 must choose between dropping to 135 or moving up to 147.

Lightweight (135 lbs / 61.2 kg)

Lightweight is where speed, skill, and punching technique often matter more than raw power. Roberto Duran built his early legend at 135, and Pernell Whitaker may have been the most technically perfect fighter ever to compete at this weight. The division remains one of boxing’s most consistently stacked classes and is retained under Zuffa’s model.

Super Featherweight / Junior Lightweight (130 lbs / 59 kg)

Floyd Mayweather Jr. began his career at 130 before moving up through the divisions. Manny Pacquiao won his third world title at this weight. The division serves as a natural bridge between featherweight and lightweight, but it is one of the nine classes Zuffa has eliminated. Fighters at 130 will need to commit to either 126 or 135.

Featherweight (126 lbs / 57.2 kg)

One of the sport’s most historically prestigious divisions. Willie Pep’s defensive wizardry, Salvador Sanchez’s tragically short career, and Prince Naseem Hamed’s showmanship all played out at 126. The division is retained under Zuffa’s model, with WBC featherweight champion Bruce Carrington among the fighters linked to the promotion through the Ring Magazine ambassador program.

Super Bantamweight (122 lbs / 55.3 kg)

Wilfredo Gomez was virtually untouchable at 122, and Naoya Inoue moved through this division on his way to becoming one of boxing’s biggest modern stars. Marco Antonio Barrera and Erik Morales both held titles at 122. Despite its talent history, the division does not exist under Zuffa’s framework. Fighters at 122 will need to drop to bantamweight at 118 or move up to featherweight at 126.

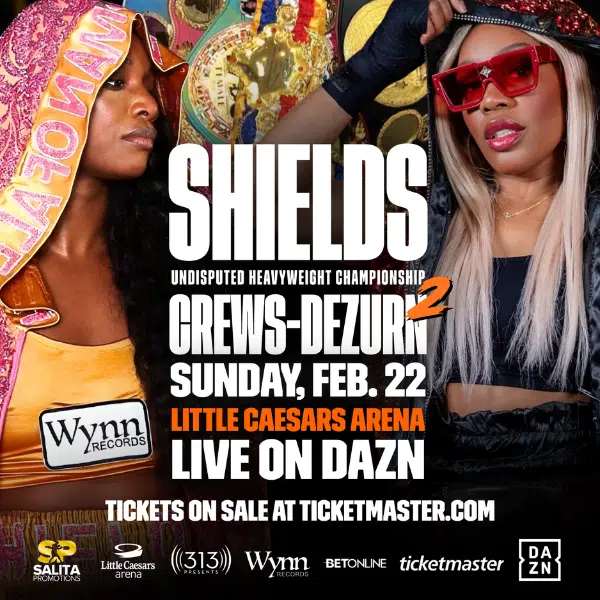

Bantamweight (118 lbs / 53.5 kg)

Bantamweight is the lowest weight class Zuffa recognizes, which means it effectively absorbs fighters from four traditional classes below it: minimumweight (105), light flyweight (108), flyweight (112), and super flyweight (115). A natural 105-pound fighter competing at 118 would be giving up 13 pounds, a substantial difference at those weights. The lower-weight divisions have deep competitive fields in countries like Thailand, Japan, Mexico, and the Philippines, where those classes draw large audiences and produce elite talent.

Flyweight (112 lbs / 50.8 kg)

Jimmy Wilde, Pancho Villa, and Roman Gonzalez represent the division’s rich history spanning more than a century. Flyweight has been one of boxing’s most consistently competitive classes, particularly in countries like Japan, Mexico, the Philippines, and Thailand. Under Zuffa’s system, flyweight does not exist — these fighters would need to move up to 118.

Super Flyweight (115 lbs / 52.2 kg)

The 115-pound class produced one of boxing’s best modern rivalries: Srisaket Sor Rungvisai vs. Juan Francisco Estrada. It is a division with passionate followings in Asia and Latin America. Not recognized by Zuffa.

Light Flyweight (108 lbs / 49 kg)

Michael Carbajal brought mainstream American attention to this weight class in the early 1990s, and Ricardo Lopez went 51-0-1 fighting primarily at 108 and 105. The division remains active internationally but is not part of Zuffa’s structure.

Minimumweight / Strawweight (105 lbs / 47.6 kg)

The lightest division in boxing was established in 1987 and has been dominated by fighters from Thailand, Japan, Mexico, and the Philippines. Wanheng Menayothin compiled a 54-0 record at minimumweight. Under Zuffa’s model, a 105-pound fighter would need to gain 13 pounds to compete at the lowest recognized class.

Zuffa Boxing’s Eight-Division Model

In February 2026, Zuffa Boxing officially confirmed it will recognize only eight weight classes. The promotion, a joint venture between TKO Group Holdings and Saudi Arabia’s Sela Sport, was founded by Dana White and Turki Alalshikh. The structure applies the UFC’s organizational model to boxing: fewer divisions, one belt per weight class, and a single championship path in each division.

The eight recognized Zuffa divisions are:

| Zuffa Division | Weight Limit | Traditional Divisions Absorbed |

|---|---|---|

| Bantamweight | 118 lbs | Minimumweight, Light Flyweight, Flyweight, Super Flyweight |

| Featherweight | 126 lbs | Super Bantamweight |

| Lightweight | 135 lbs | Super Featherweight |

| Welterweight | 147 lbs | Super Lightweight / Jr. Welterweight |

| Middleweight | 160 lbs | Super Welterweight / Jr. Middleweight |

| Light Heavyweight | 175 lbs | Super Middleweight |

| Cruiserweight | 200 lbs | None |

| Heavyweight | 200+ lbs | None |

Structure and Rankings

The UFC operates with eight men’s weight classes (flyweight through heavyweight), and Zuffa Boxing’s eight-division model mirrors that structure. The promotion uses Ring Magazine rankings to determine contenders and matchups within each division, with plans to eventually develop its own internal rankings system. All twelve Zuffa Boxing events scheduled for 2026 are set to broadcast exclusively on Paramount+, with select cards simulcast on CBS.

Zuffa Boxing crowns its first champion on March 8, 2026, when IBF cruiserweight titleholder Jai Opetaia faces Brandon Glanton at the Meta APEX in Las Vegas. Each of the eight divisions will have a single Zuffa belt with one champion — no interim titles, no secondary straps.

How the Divisions Map

Fighters who have competed in the nine eliminated weight classes face a straightforward choice under the Zuffa system: move up or move down to the nearest recognized division.

At 140 pounds, a fighter either drops five pounds to make lightweight at 135 or adds seven to compete at welterweight at 147. At 154, the options are middleweight at 160 or welterweight at 147. Super middleweights at 168 must choose between middleweight at 160 and light heavyweight at 175. Callum Walsh, who had been fighting at 154, moved up to 160 for his Zuffa debut against Carlos Ocampo.

The consolidation is most significant at the lower end of the scale. Bantamweight at 118 is the lowest division Zuffa recognizes, which absorbs fighters from four traditional classes: minimumweight (105), light flyweight (108), flyweight (112), and super flyweight (115). A natural 105-pound fighter competing at 118 would be giving up 13 pounds, a substantial difference at those weights. The lower-weight divisions have deep competitive fields in countries like Thailand, Japan, Mexico, and the Philippines, where those classes draw large audiences and produce elite talent.

Zuffa Boxing and the Traditional System

Zuffa’s eight-division system operates alongside the traditional 17-class structure. The WBC, WBA, IBF, and WBO continue to recognize and crown champions in all 17 divisions. State athletic commissions across the United States also recognize all traditional weight classes, and the majority of professional boxing — from club shows to major promotions — continues to operate within the existing framework.

Zuffa Boxing does not recognize titles from other sanctioning bodies and controls its own championship lineage within each division. However, the promotion has indicated flexibility in some cases. Jai Opetaia, who holds the IBF cruiserweight title, has said his goal is to unify the division, and Dana White confirmed Zuffa will work with other sanctioning bodies to support that effort.

The promotion has signed or been linked to fighters across multiple divisions, including Callum Walsh at middleweight, Serhii Bohachuk, Radzhab Butaev at welterweight, Efe Ajagba at heavyweight, and Jose Valenzuela. Several Ring Magazine brand ambassadors — including WBC featherweight champion Bruce Carrington and WBO lightweight champion Charlotte Mason — have also been connected to the Zuffa ecosystem.

The Bottom Line

Boxing’s 17 weight classes developed over more than a century to create competitive balance, protect fighter safety, and serve the global diversity of the sport. The lower-weight divisions remain active and highly competitive, particularly in Asia and Latin America, where they draw large audiences and produce world-class talent.

Zuffa Boxing’s eight-division model represents a different approach to organizing the sport. It consolidates nine traditional weight classes into the nearest recognized division, creating a streamlined championship structure with one belt per weight class. The traditional 17-division system continues to operate across the four major sanctioning bodies and state athletic commissions.

Both systems are now running in parallel. How fighters, managers, and promoters navigate between them will shape the competitive landscape of professional boxing in the years ahead.