No place on earth — not Brooklyn, not Philly, not Mexico City — produces world champion boxers at the rate Puerto Rico does. First in the world in champions per capita. An island of 3.2 million people that has minted title holders in all 17 weight classes. Let that sink in. Every. Single. Division.

From the coquí-filled mountains of Vega Alta to the streets of Caguas and Carolina, the island doesn’t just love boxing — it breathes it. Puerto Rican fighters don’t come to participate. They come to take over divisions, pack out Madison Square Garden, and carry a nation’s flag into war every time they step between the ropes. If you’re looking for the best boxers from Puerto Rico, understand something first: this isn’t a list. It’s a Hall of Fame wing.

Félix “Tito” Trinidad

Welterweight / Jr. Middleweight / Middleweight | Cupey Alto, PR | 42-3, 35 KOs

There has never been a fighter who carried the weight of an entire island the way Tito Trinidad did. When he walked into Madison Square Garden, the building shook — literally. Puerto Rican flags as far as you could see, “TITO!” chants rattling the steel beams, grown men crying before the first bell even rang. He wasn’t just a boxer. He was a movement. And that left hook? Good night. Ask Oscar De La Hoya, who thought he won that fight until the scorecards reminded him that Tito’s pressure is a verdict in itself. Ask Fernando Vargas, who got unified right out of consciousness. Ask William Joppy, who got demolished inside five rounds at The Garden in what might have been the peak of Tito Mania.

Trinidad held the IBF welterweight title for nearly seven years with 15 defenses — the second-longest welterweight reign in history. He moved up and unified at 154, then had the audacity to challenge Bernard Hopkins at middleweight. He lost that one, and Hopkins deserves every bit of credit for that masterclass, but Tito’s willingness to fight anyone, anywhere, at any weight is what separates legends from champions. Ring Magazine Fighter of the Year in 2000. International Boxing Hall of Fame, Class of 2014. The pride of Cupey Alto forever.

Miguel Cotto

Jr. Welterweight / Welterweight / Jr. Middleweight / Middleweight | Caguas, PR | 41-6, 33 KOs

Miguel Cotto didn’t talk. He didn’t need to. The man built a legacy on tough fights and few words, and the resume speaks at a volume that drowns out every trash-talker who ever laced up gloves. First Puerto Rican to win world titles in four weight classes. A body puncher so vicious that opponents would quit on their stools rather than take another shot to the ribs. When Cotto fought at Madison Square Garden, it wasn’t an event — it was a national holiday for the Puerto Rican diaspora in New York.

The Caguas product beat Shane Mosley, Zab Judah, Paulie Malignaggi, and Sergio Martinez. He gave Floyd Mayweather some of the toughest rounds of his career at 154. And the Margarito rematch? Ten rounds of righteous vengeance that still holds up as one of the most satisfying fights in boxing history. Cotto sold more tickets at Madison Square Garden in this century than any other fighter. He retired in 2017 as quiet and dignified as the day he started — and as dangerous as anyone who ever fought out of Puerto Rico.

Amanda Serrano

Featherweight (7 weight classes) | Carolina, PR (raised in Brooklyn) | 48-4-1, 31 KOs

Amanda Serrano didn’t just break through the glass ceiling in women’s boxing — she put her fist through it and kept swinging. Nine world titles across seven weight classes. A Guinness World Record holder. The only Puerto Rican fighter — male or female — to win titles in more than four divisions. That record she holds for most weight classes conquered? It might never be touched. She went from super flyweight to super lightweight over her career, dominating everywhere she stopped. Born in Carolina, raised in Brooklyn, beloved by both, Serrano is the modern standard-bearer for Puerto Rican boxing excellence.

The Katie Taylor rivalry defined an era. Their first fight at Madison Square Garden in 2022 was the biggest women’s boxing event in history. Their trilogy fight in July 2025 headlined the first all-women’s card at The Garden, broadcast on Netflix to over 300 million subscribers. Serrano returned to Puerto Rico in January 2026 to defend her unified featherweight titles at the Coliseo Roberto Clemente in San Juan — a homecoming queen in the truest sense. Five-time WBAN Fighter of the Year, Ring 8 Fighter of the Decade. She’s not done yet, and the island isn’t done cheering.

Wilfredo Gómez

Jr. Featherweight / Featherweight / Jr. Lightweight | Las Monjas, PR | 44-3-1, 42 KOs

“Bazooka” didn’t just knock people out — he obliterated them with a frequency that borders on absurd. Gómez started his career with a draw, then won his next 32 fights — all by stoppage. Read that again. Thirty-two consecutive knockouts. He made 17 consecutive title defenses at super bantamweight, every single one ending early. That’s not a title reign. That’s a crime spree. He smashed Carlos Zarate, destroyed Lupe Pintor in an all-time classic in New Orleans, and ran through the 122-pound division like it owed him money.

The only blemish on his super bantamweight run was moving up to featherweight to challenge the magnificent Salvador Sanchez — and even in that loss, Gómez rallied from a horrific first-round knockdown to make it competitive before being stopped in the eighth. He later won titles at featherweight and junior lightweight, cementing himself as one of the most devastating punchers pound-for-pound in boxing history. If you want to understand why Puerto Rico worships its fighters, watch Wilfredo Gómez highlights. Then try to pick your jaw up off the floor.

Wilfred Benítez

Jr. Welterweight / Welterweight / Jr. Middleweight | San Juan, PR (raised in Bronx) | 53-8-1, 31 KOs

The youngest world champion in boxing history. Seventeen years old. Let that marinate. While other kids his age were worrying about prom, Wilfred Benítez was outpointing Antonio Cervantes — a man with 42 knockouts — to win the WBA junior welterweight title. “El Radar” had a defensive genius that defied physics. He slipped punches like he could see the future, made elite fighters miss by millimeters, and countered with surgical precision. Boxing historian Jim Jacobs called him one of the most naturally gifted fighters he’d ever witnessed.

Benítez won titles at 140, 147, and 154 pounds before he turned 24. He outpointed Carlos Palomino for the welterweight crown. It took Sugar Ray Leonard until six seconds before the final bell to stop him — that’s how hard this kid was to hit. Tragically, the punishment he absorbed later in his career has left him requiring full-time care, a devastating reminder of the sport’s cruelty. He remains a legend in need — and a legend, period. Hall of Fame, Class of 1996.

Héctor “Macho” Camacho

Jr. Lightweight / Lightweight / Jr. Welterweight | Bayamón, PR (raised in Spanish Harlem) | 79-6-3, 38 KOs

Before Floyd Mayweather made defensive wizardry look stylish, Héctor Camacho was doing it in sequined trunks and a headband, talking trash the entire time. “Macho” was pure box office — a flashy southpaw with blinding hand speed who could make world-class fighters look like they were swinging at smoke. He beat José Luis Ramirez, Edwin Rosario, Ray Mancini, and Freddie Roach. He sent Sugar Ray Leonard into permanent retirement and beat Roberto Durán twice. Three-division champion who stayed active until age 48 because he simply loved fighting that much.

Born in Bayamón and raised in Spanish Harlem, Camacho bridged Puerto Rico and New York in a way few fighters ever have. He was the prototype for the flashy, defensive Puerto Rican fighter — all speed, angles, and personality. His tragic murder in 2012 robbed boxing of one of its most colorful characters, but anyone who watched “Macho” in his prime at 130 and 135 knows they were watching something special. Nearly 80 wins in a 30-year career. Never stopped. Never boring.

Carlos Ortiz

Jr. Welterweight / Lightweight | Ponce, PR (raised in New York) | 61-7-1, 30 KOs

Before Tito, before Cotto, before any of them — there was Carlos Ortiz. The first great Puerto Rican boxing superstar, and arguably the finest lightweight of the 1960s. Ortiz held the lightweight title from 1962 to 1968, with only a brief interruption, and he beat a who’s who of Hall of Famers along the way: Joe Brown, Flash Elorde, Sugar Ramos. He fought in New York, London, Tokyo, Panama, the Philippines, and anywhere else they’d put up a ring, because Carlos Ortiz didn’t duck anybody and didn’t care about home-field advantage.

When Ortiz fought at Madison Square Garden, thousands of fans from Spanish Harlem would pack the arena — the blueprint for what Tito and Cotto would later take to stratospheric levels. He became the first Puerto Rican inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1991, a pioneer who proved that a kid from Ponce could take on the world and win. The New York Times once described him as “Puerto Rico’s contribution to the Fighting Irish Regiment.” The man fought everywhere, feared no one, and built the foundation that every Puerto Rican champion since has stood on.

Edwin Rosario

Lightweight / Jr. Welterweight | Toa Baja, PR | 47-6, 42 KOs

“El Chapo” Rosario was a heat-seeking missile at 135 pounds — a power puncher from Toa Baja who held different versions of the lightweight title three times during the 1980s. In an era stacked with elite lightweights, Rosario stood out because he could genuinely crack. He beat Livingstone Bramble, Olympic gold medalist Howard Davis Jr., and fought every top name at the weight. The losses? Julio César Chávez (the greatest Mexican fighter ever), Héctor Camacho (split decision), and a couple of coin-flip wars with Frankie Randall and Juan Nazario.

Rosario’s career defined the golden age of the Mexico-Puerto Rico rivalry. He and Camacho fighting for Puerto Rican lightweight supremacy, while Chávez waited on the other side of the divide — that’s the kind of era that boxing people still talk about with reverence. Forty-two knockouts in 53 fights. At his best, “El Chapo” was one of the most dangerous fighters on the planet at any weight.

Wilfredo Vázquez

Bantamweight / Jr. Featherweight / Featherweight | Bayamón, PR | 56-9-2, 41 KOs

“El Nene” Vázquez was the definition of a Puerto Rican road warrior — a three-division world champion who’d fight anybody, anywhere, and usually find a way to get his hand raised. He won the WBA bantamweight title, then moved up to super bantamweight and became a dominant force, before capturing the WBA featherweight belt for good measure. One of only six Puerto Rican fighters to win titles in three different weight classes, a feat that speaks to his adaptability and his power. Vázquez could box, he could bang, and he carried his punching power up through the divisions.

He held the WBA super bantamweight title for the better part of a decade and defended it against all comers. His only loss at that weight came against the brilliant Naseem Hamed in 1998, and even that was a competitive fight. “The Pride of Puerto Rico” retired in 2002, leaving behind a legacy that his son, Wilfredo Vázquez Jr., would later attempt to carry forward at featherweight. The bloodline is real.

Subriel Matías

Jr. Welterweight | Fajardo, PR | 21-2, 21 KOs

If you want to understand what Puerto Rican boxing passion looks like in 2026, watch Subriel Matías fight. Or rather, watch him stalk his opponent with his hands down, hair dyed, jewelry gleaming under the ring lights — then erase them with body shots that make you wince through a television screen. Every single one of his 21 wins has come by knockout. Every. Single. One. He doesn’t know what a decision looks like, and he doesn’t want to learn. His destruction of Jeremiah Ponce for the IBF junior welterweight title was a masterpiece in controlled violence.

Born in Fajardo, Matías represents the next generation of Puerto Rican fighters — the ones who grew up watching Tito and Cotto and decided they wanted that level of adoration. He’s tasted defeat against Liam Paro and Dalton Smith, but the relentless, terrifying style remains. When Matías fights in Puerto Rico, the island stops. He is the heartbeat of Puerto Rican boxing right now, and the 140-pound division knows it.

Esteban De Jesús

Lightweight | Carolina, PR | 57-5, 32 KOs

Before anyone else did it, Esteban De Jesús beat Roberto Durán. Let that register. In November 1972, De Jesús outpointed the great “Manos de Piedra” — handing Durán his first professional loss. He was that good. A slick southpaw from Carolina with beautiful timing and enough power to keep anyone honest, De Jesús held the WBC lightweight title and went 2-1 against Durán in one of boxing’s most underappreciated trilogies. The lightweight division in the 1970s ran through him whether historians acknowledge it or not.

De Jesús’ life outside the ring was marked by tragedy — addiction and a murder conviction cut short what should have been a far longer legacy. He died in prison in 1989 from AIDS-related illness at just 37 years old. But inside the ropes, the kid from Carolina was as talented as any lightweight who ever lived, and that first Durán victory remains one of the most significant wins in Puerto Rican boxing history.

José “Chegüi” Torres

Light Heavyweight | Ponce, PR | 41-3-1, 29 KOs

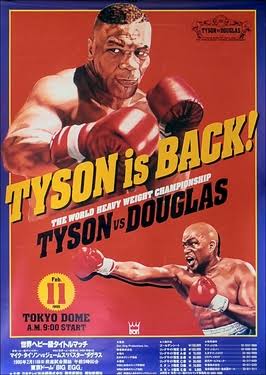

Torres won a silver medal at the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne, then came stateside and knocked out Willie Pastrano for the light heavyweight championship of the world. Trained by the legendary Cus D’Amato — the same man who later molded Mike Tyson — Torres was a peek-a-boo stylist with real power and serious boxing IQ. He defended his title three times before losing it to Dick Tiger, and his post-career was as remarkable as anything he did in the ring: he became Chairman of the New York State Athletic Commission, a published author, and a respected journalist. The first Puerto Rican to hold a light heavyweight world title, and one of the most intellectually gifted men to ever lace up gloves.

Pedro Montañez

Lightweight / Welterweight | Cayey, PR | 92-7-4, KOs N/A

“El Torito de Cayey” — The Little Bull of Cayey — was Puerto Rico’s first genuine boxing superstar, emerging in the 1930s as a top-ranked contender who piled up 50 consecutive victories at a time when the sport was still technically illegal on the island. Montañez never won an official world title, but he fought in an era when politics and racial barriers kept deserving fighters from championship opportunities. He was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2007, a long-overdue recognition for the man who proved that Puerto Rico belonged on boxing’s world stage. Ninety-two wins across 103 fights. The foundation was laid right here.

Juan Manuel López

Jr. Featherweight / Featherweight | Río Piedras, PR | 36-6, 32 KOs

“Juanma” López was supposed to be the next Tito Trinidad — and for a couple of years, he looked like he might actually deliver on that impossible billing. A 2004 Olympian who turned pro and tore through the super bantamweight division with knockout power that bordered on ridiculous, López won the WBO title at 122 and then moved up to take the WBO featherweight belt. His knockouts were spectacular, his popularity in Puerto Rico was soaring, and the comparisons to the island’s greatest were flying. Then Orlando Salido happened. Twice. The losses exposed durability issues that derailed a once-brilliant career, but at his peak, Juanma was a knockout artist as exciting as anyone in the sport.

John Ruiz

Heavyweight | Methuen, MA (parents from PR) | 44-9-1, 30 KOs

Say what you want about John Ruiz’s style — and people have said plenty — but “The Quiet Man” was the first Latino heavyweight champion in boxing history. He beat Evander Holyfield for the WBA title in 2001 and defended it multiple times against top-level competition. Born in Massachusetts to Puerto Rican parents, Ruiz embraced his heritage and fought with the Puerto Rican flag draped around his shoulders. He wasn’t flashy, he wasn’t a knockout artist, but he was tough, durable, and he won a world heavyweight title. In a division where Puerto Ricans rarely compete, Ruiz did something nobody else from the island had ever done.

Why Puerto Rico Keeps Producing Champions

There’s something in the water in Puerto Rico — or maybe in the culture. Boxing isn’t just a sport on the island. It’s identity. It’s inherited. Kids grow up watching Tito highlights the way mainland American kids watch football. The gyms in San Juan, Caguas, Bayamón, and Carolina produce talent at a rate that defies the island’s size, and the diaspora communities in New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago extend the pipeline even further.

Puerto Rico ranks first in the world in boxing champions per capita. The island has produced world titleholders in all 17 weight divisions. The search for the next great Puerto Rican star is a permanent storyline in boxing media because the island always delivers one. The Mexico-Puerto Rico rivalry remains the fiercest national grudge match in the sport, producing mega-events that fill arenas and drive pay-per-view numbers.

Brooklyn’s got its heavyweights. Detroit’s got the Kronk legacy. Philly’s got its gym warriors. But Puerto Rico? Puerto Rico has a whole island of fighters, an unbroken chain of world champions stretching back to the 1930s, and a fan base that turns every fight into a national event. Three million people. More world champions than countries ten times their size. That’s not a boxing tradition. That’s a boxing dynasty.