When the Odds Get It Wrong

Oddsmakers are sharp. They have access to fight film, training camp intelligence, historical data, and the collective wisdom of millions of dollars in betting action. Most of the time, the favorite wins. But boxing is the one sport where a single moment — one punch landed clean on the chin — can render all of that analysis meaningless.

That volatility is what makes boxing unique in the betting landscape. In football, a 20-point underdog almost never wins. In boxing, a 20-to-1 underdog doesn’t just win — he knocks out the most feared man on the planet in front of the entire world.

This is the definitive account of the fights where the odds were wrong, what the market missed, and what each upset teaches anyone trying to understand how boxing betting really works.

Buster Douglas vs. Mike Tyson — Tokyo, February 11, 1990

The Odds: 42-to-1

No betting upset in any sport has ever matched this one, and it’s unlikely anything ever will. Mike Tyson entered the Tokyo Dome as the undisputed heavyweight champion of the world with a 37-0 record, 33 knockouts, and a reputation as the most terrifying fighter since prime Sonny Liston. He had destroyed Michael Spinks in 91 seconds. He had stopped Larry Holmes in four. Opponents looked beaten before the opening bell.

James “Buster” Douglas was a talented but inconsistent heavyweight from Columbus, Ohio. He had a solid jab, good size at 6’4”, and legitimate skills — but he had quit in previous fights, most notably against Tony Tucker. The boxing world viewed him as a capable but mentally fragile fighter who would fold under pressure. Several major sportsbooks in Las Vegas didn’t even post odds on the fight because they considered it so one-sided that taking action would be irresponsible.

The ones that did post it listed Douglas somewhere between 35-to-1 and 42-to-1. For context, those are the kind of odds you’d see on a mid-major college basketball team winning the national championship.

What the Odds Missed

Douglas’s mother, Lula Pearl, had died 23 days before the fight. His personal life was in turmoil. To the oddsmakers, these were additional reasons to dismiss him — emotional distraction typically hurts performance. But Douglas channeled his grief into the most focused performance of his career. He later said he fought that night for his mother.

Meanwhile, Tyson’s preparation was a disaster. He was in the middle of his divorce from Robin Givens, his relationship with trainer Kevin Rooney had dissolved, and reports from Tokyo indicated he spent more time in the city’s nightlife than in the gym. His new cornermen — Aaron Snowell and Jay Bright — lacked the tactical depth of Rooney. None of this was secret information, but the market discounted it because Tyson’s aura seemed invincible.

The Fight

Douglas fought the fight of his life. He established the jab from the opening round, used his four-inch reach advantage to keep Tyson at distance, and threw combinations when Tyson tried to close the gap. By the middle rounds, it was clear that Tyson had no Plan B. His corner couldn’t make adjustments because they didn’t have the experience.

Tyson did knock Douglas down in the 8th round with a right uppercut — and the controversial long count (the referee reached “9” but Douglas may have been down for 11-12 seconds by the arena clock) became the most debated sequence in boxing history. But Douglas got up and continued to dominate.

In the 10th round, Douglas landed a four-punch combination — jab, right hand, left hook, right uppercut — that put Tyson on the canvas for the first time in his career. Tyson fumbled for his mouthpiece on his hands and knees. The count reached ten. The most feared heavyweight champion in the world had been knocked out by a 42-to-1 underdog.

Several sportsbooks initially refused to honor the bets, citing the long count controversy. They eventually paid. The few bettors who had the foresight — or the audacity — to back Douglas made a fortune.

The Lesson

Never discount personal motivation. Never assume that a dominant champion’s aura is a substitute for preparation. And always look at the corner — the team behind the fighter matters enormously. If you understand how boxing odds are set, you know that oddsmakers rely heavily on past performance. Douglas’s past said he would quit. His present said otherwise.

Lennox Lewis vs. Hasim Rahman — Carnival City, South Africa, April 22, 2001

The Odds: 20-to-1

Lennox Lewis was the lineal heavyweight champion and widely considered the best big man in the world. Rahman was a solid but unspectacular heavyweight with a 36-2 record and respectable power but no signature wins. This was supposed to be a routine title defense — a pit stop before a megafight with Mike Tyson.

Lewis reportedly agreed to fight in South Africa at elevation (5,750 feet in Brakpan) for a combination of promotional and financial reasons. He was also filming a role in the movie “Ocean’s Eleven” during training camp, splitting his attention between the set and the gym.

What the Odds Missed

Altitude is a real factor in boxing. At 5,750 feet, the reduced oxygen affects stamina, recovery between rounds, and a fighter’s ability to sustain a high work rate. Lewis trained at altitude for only a few weeks — not nearly enough time to fully acclimate. Rahman, meanwhile, had prepared specifically for the conditions.

The bigger issue was Lewis’s mindset. Multiple reports from camp suggested he wasn’t taking the fight seriously. He was looking past Rahman to the Tyson payday. In a sport where concentration lapses are measured in fractions of a second, that kind of mental absence is lethal.

The Fight

Lewis controlled the early rounds but looked sluggish and heavy-legged — consistent with a fighter struggling at altitude. In the 5th round, Rahman landed a straight right hand over Lewis’s lazy jab. It was a clean, concussive shot, and Lewis went down face-first. He was counted out.

The boxing world was stunned, but the warning signs were all there for anyone paying attention. Lewis won the rematch emphatically, knocking Rahman out in the 4th round of a November 2001 fight in Las Vegas — at sea level, with full focus, and with something to prove.

The Lesson

Location matters. Preparation matters. And when a fighter is looking past his opponent, the market should adjust more aggressively than it typically does. This fight is a textbook case for anyone analyzing boxing betting strategy — the variables were visible, but the public ignored them because of Lewis’s resume.

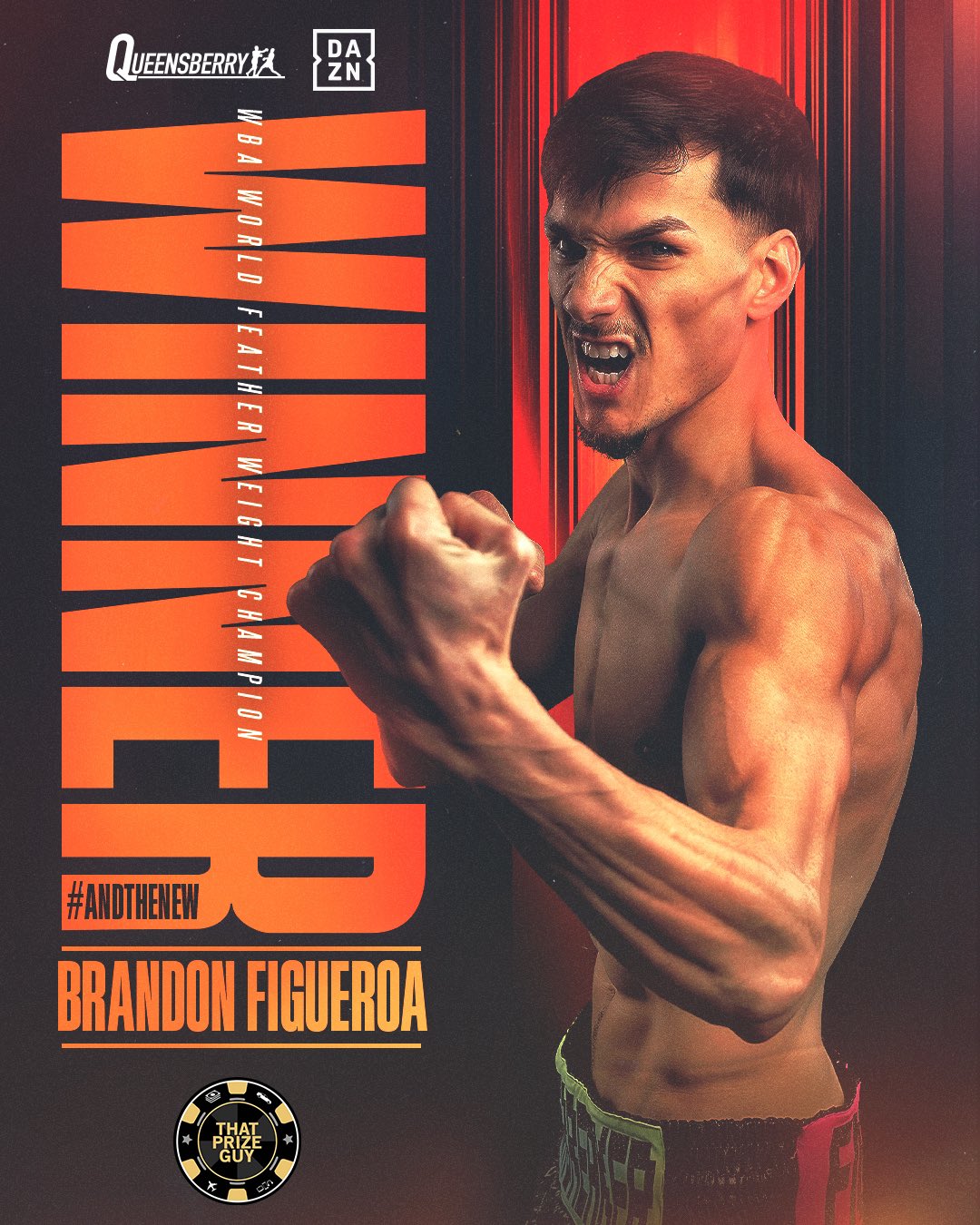

Andy Ruiz Jr. vs. Anthony Joshua I — Madison Square Garden, June 1, 2019

The Odds: 25-to-1

Anthony Joshua held three of the four major heavyweight titles and was making his highly anticipated U.S. debut at the Mecca of Boxing. He was tall, chiseled, powerful, and had knocked out 21 of his 22 opponents. The event was designed as a coronation — Joshua’s formal introduction to the American market.

Andy Ruiz Jr. was a late replacement after Jarrell Miller failed multiple drug tests. Ruiz had a 32-1 record with legitimate skills but came into the fight with a soft, round physique that made him easy to dismiss visually. The narrative was clear: Joshua was a Greek god fighting a guy who looked like he’d been eating tacos in the parking lot.

What the Odds Missed

Ruiz was a former amateur standout with fast hands, a solid chin, and genuine heavyweight power — he just didn’t look the part. His hand speed was actually faster than Joshua’s, a fact that film study would have revealed. He was also a natural heavyweight who didn’t drain himself making weight, while Joshua’s muscular frame required careful weight management.

More importantly, Ruiz had nothing to lose. He took the fight on short notice, was getting a career-high payday regardless of the result, and was fighting in front of a largely ambivalent crowd (most tickets were sold when Miller was the opponent). The pressure was entirely on Joshua.

Joshua, meanwhile, was dealing with the weight of expectations — first fight in America, massive promotional buildup, the pressure of a global audience. For all his physical gifts, Joshua had shown chin vulnerability in a previous fight against Wladimir Klitschko (where he was dropped in the 6th round before rallying to win).

The Fight

Joshua actually dropped Ruiz in the 3rd round. For a moment, it looked like the script would hold. But Ruiz got up and immediately dropped Joshua twice in the same round with rapid-fire combinations. Joshua never fully recovered. Ruiz dropped him two more times, and the fight was stopped in the 7th round.

The boxing world collectively lost its mind. It was the biggest heavyweight upset since Douglas-Tyson, and it happened on the biggest possible stage.

Joshua won the rematch six months later in Saudi Arabia by boxing cautiously from the outside — essentially admitting that he couldn’t fight Ruiz on the inside. The rematch was technically sound but boring, which told you everything about how dangerous Ruiz was at close range.

The Lesson

Never judge a fighter by his physique. Look at hand speed, amateur pedigree, chin durability, and how a fighter performs under pressure. The public bet the body, not the fighter. The sharps who looked deeper saw a live underdog.

Leon Spinks vs. Muhammad Ali — Las Vegas, February 15, 1978

The Odds: 10-to-1

Muhammad Ali was a three-time heavyweight champion, the most famous athlete in the world, and still considered the gold standard of the division despite being 36 years old with visible physical decline. Leon Spinks was a 24-year-old Olympic gold medalist with only seven professional fights on his record. Seven. He had never fought a 15-round fight. The idea that he could outwork the greatest of all time over the championship distance seemed absurd.

What the Odds Missed

Ali was old. Not “getting old” — old for a heavyweight by 1978 standards. His legs were gone, his reflexes had slowed, and he had been through wars with Joe Frazier, Ken Norton, and Earnie Shavers that left cumulative damage. He had also stopped training with the intensity that defined his earlier career, relying on his name and ring intelligence to compensate for physical decline.

Spinks, on the other hand, was young, hungry, and brought relentless pressure. His amateur pedigree — gold medal at the 1976 Montreal Olympics — indicated elite-level talent even if his pro resume was thin. He also had an unorthodox, swarming style that made him awkward to deal with.

The Fight

Spinks pressed the action from the opening bell and never let Ali rest. Ali tried to use the ropes, tried to counter, tried to use ring generalship — but his legs couldn’t carry him for 15 rounds of constant pressure. Spinks won a split decision in one of the most shocking results of the era.

Ali won the rematch seven months later, making him the first three-time heavyweight champion. But the Spinks upset proved that youth, activity, and pressure can overwhelm experience and legacy — a lesson that applies to every generation of boxing.

The Lesson

Aging fighters are the most consistently overvalued commodity in boxing betting. The public bets the name, the legacy, the highlight reel. The market should bet the current fighter standing in the ring on fight night.

Corrie Sanders vs. Wladimir Klitschko — Hanover, Germany, March 8, 2003

The Odds: 14-to-1

Wladimir Klitschko was a rising heavyweight contender with a 40-1 record and fearsome power. Sanders was a 37-year-old South African with a 38-2 record who was primarily known on the regional circuit and spent most of his time playing golf. He was a natural southpaw with legitimate one-punch power, but few observers gave him any chance against the younger, bigger Klitschko.

What the Odds Missed

Klitschko had a well-documented chin problem at that stage of his career. He had been stopped by Corrie’s countryman Ross Puritty and had shown vulnerability to hard shots in several other fights. The knock on Klitschko was that his technical skills abandoned him when he was hurt — he would revert to survival mode and often couldn’t recover.

Sanders was a southpaw with explosive power in his left hand. Southpaw-versus-orthodox matchups create natural angles for the left cross — the power punch lands from an angle that orthodox fighters often struggle to see coming. Against a fighter with a suspect chin, that combination was dangerous.

The Fight

Sanders dropped Klitschko in the first 10 seconds of the fight. It set the tone. He dropped him again, and again, and the fight was stopped in the second round. The speed of the destruction shocked the boxing world, but the elements — southpaw power vs. chin vulnerability — were identifiable in advance.

Klitschko would later reinvent himself under trainer Emanuel Steward, fixing his defensive flaws and becoming the dominant heavyweight champion of the next decade. But on that night in Hanover, the market paid the price for betting the resume instead of analyzing the stylistic matchup.

The Lesson

Stylistic analysis beats record analysis every time. A fighter’s record tells you how many times he won — it doesn’t tell you how he handles a specific type of opponent. As any student of boxing betting strategy knows, styles make fights. A 14-to-1 line on a southpaw power puncher against a fighter with a known chin issue was a gift.

Upset Patterns: What the Market Consistently Undervalues

Looking across these upsets and dozens of others throughout boxing history, clear patterns emerge in what the betting market tends to miss:

Aging Champions

The public overvalues name recognition and past accomplishments. A fighter’s last five performances matter more than his career highlight reel. Physical decline — particularly in hand speed, reflexes, and punch resistance — is often visible on film before it shows up in the betting line. Ali-Spinks is the archetype, but this pattern repeats across every era.

Overlooked Opponents

When a champion is publicly focused on a bigger fight down the road, the current opponent becomes dangerous. Lewis-Rahman is the clearest example, but it happens at every level of the sport. At club shows like the ones at Tropicana Atlantic City, you see it too — a prospect looking past a tough journeyman can get caught.

Physical Mismatches That Cut Both Ways

The public assumes bigger and more muscular means better. Ruiz-Joshua proved that hand speed, low center of gravity, and inside fighting ability can neutralize a significant size advantage. Sanders-Klitschko showed that southpaw angles exploit specific defensive weaknesses regardless of the size differential.

Camp and Preparation Red Flags

Trainer changes, camp disruptions, short-notice opponent switches, fighting at altitude without proper acclimation, and divided attention (Lewis filming a movie) are all quantifiable risk factors that the market underweights because they’re harder to put into a spreadsheet than win-loss records.

Motivation Gaps

A fighter with nothing to lose against a fighter with everything to lose creates a dangerous dynamic. Douglas was fighting for his mother. Ruiz was a lottery-ticket replacement with no pressure. Spinks was a hungry Olympian with something to prove. In every case, the underdog was more invested in the outcome than the favorite — and the line didn’t reflect it.

What Upsets Mean for the Educated Fan

You don’t need to place a single wager to benefit from understanding upsets. Knowing why the market gets it wrong makes you a sharper observer of the sport. When you watch a fight card — whether it’s a world championship pay-per-view or a club show at Tropicana Atlantic City — you start to see the variables that casual viewers miss.

Is the favorite looking past this fight? Did the underdog switch trainers and show improvement in his last camp? Is the favorite fighting a style that historically gives him trouble? These are the questions that separate informed fans from casual ones.

The odds are a tool. They tell you what the market thinks. But the market is made up of people, and people have blind spots. The history of boxing is a history of those blind spots getting exposed — one punch at a time.

The Complete BoxingInsider.com Betting Series

Boxing Betting Explained: The Complete Guide

How odds work, every bet type, strategy basics, and famous upsets — start here.

The Biggest Boxing Betting Upsets of All Time

Douglas-Tyson, Ruiz-Joshua, and more — what the odds missed and why it matters.

How Boxing Odds Are Set: Behind the Line

How oddsmakers build lines, what moves them, and what line movement tells you.

Boxing Prop Bets & Round Betting Explained

Round picks, method of victory, knockdown props, and every exotic wager broken down.

Live Boxing Betting, Parlays & Advanced Strategy

In-fight odds, parlay math, expected value, and the concepts sharp observers use.

Boxing Betting vs. Other Sports

How boxing compares to NFL, NBA, MLB, and MMA — and why boxing rewards knowledge most.

BoxingInsider.com is a boxing news and entertainment website. We do not operate a gambling platform, accept wagers, or link to sportsbooks. All odds-related content is for informational and entertainment purposes only. If you or someone you know has a gambling problem, call the National Council on Problem Gambling helpline at 1-800-522-4700.